What Is a Book? Part One

Wilderness, liminal space, and Ursula K. Le Guin’s The Left Hand of Darkness

In my last essay, I argued that we have forgotten how to read, that we have forgotten what books are, and what they do. What is a book, then? I hope this year to explore a few metaphors that will help to illuminate this question. Metaphors, not answers; illumination, not definition: this is important. My first metaphor: a book is a wilderness.

But before we get to the wilderness, I think we need to start with liminal space.

The adjective “liminal” is sometimes used to describe an in-between space, like an airport; in an airport I am neither at home nor at my destination. I am in a place of waiting. But liminal space properly means something more specific than any in-between place; the word “liminal” comes from the Latin word “limen,” which means threshold, and the concept of liminality was first developed by folklorists and anthropologists to describe the middle stage of a rite of passage, in which a threshold has been crossed but the person is not yet what they will later become. A liminal space is therefore nothing less than a doorway to a place of change that will lead to a new way of being.

A threshold or a doorway is not an adequate metaphor in itself for what books are and do. Books have, I know, been described as doorways, often usefully, but that is not what I want to get at; if books are doorways, that might suggest that once you open a book, you will already, and automatically, have arrived at a new place. Books-as-doorways also begins to sound like books are means of escapism, a word I will admit to wrestling with. Some books are, in fact, only escapism, and those are the ones I (to be honest) tend to judge as less worthy of time and attention, less worthy of re-reading. But I also try frequently to remind myself, as a guard against judging a book too quickly, that Professor J.R.R. Tolkien, in his excellent Andrew Lang lecture, “On Fairy-Stories,” described escapism as one of the positive uses of fantasy literature. “Why should a man be scorned, if, finding himself in prison, he tries to get out and go home?” Tolkien said. “Or if, when he cannot do so, he thinks and talks about other topics than jailers and prison-walls? The world outside has not become less real because the prisoner cannot see it.”1

Tolkien warns us not to “confound the escape of the prisoner with the flight of the deserter.” That is the key line for me: and why Tolkien and I are, I think, actually talking about the same thing. Books that I judge as being only escapist are ones that seem to me to point away from reality, that are a desertion from dealing with reality (escapist books, by the way, are not the only method that we use in modern life to try to desert from reality—this is a widespread and pernicious tendency in most of us these days). Tolkien’s escapist stories were to him a reminder of an outside or greater reality that cannot be seen, a reminder that cooperation and justice and love and sacrifice are in fact closer to a true picture of reality than, say, trench warfare. Think of Sam in the middle of Mordor in The Return of the King seeing a star above the dark clouds and “The beauty of it smote his heart . . . For like a shaft, clear and cold, the thought pierced him that in the end the Shadow was only a small and passing thing: there was light and high beauty forever beyond its reach.”2 Most of us will agree, whatever we think the greater reality consists of, that there is something—truth, freedom, morality, the divine—bigger than the daily news headlines, or the little circumstances that make up our day-to-day, and that this something is the true “home” to us. Ursula K. Le Guin, a writer I had the immense joy of working with as an editor, said in her National Book Award acceptance speech for the Medal for Distinguished Contribution to American Letters that “We will need writers who can remember freedom: poets, visionaries—the realists of a larger reality.”3

A book, and a liminal space, is more than a doorway. A book, ideally, is a piece of that larger reality. But both start with a doorway: a threshold that has to be crossed. In order to enter the liminal space of a book, the reader must surrender, or yield, to the experience of the book: that is the threshold. As I wrote previously, reading takes risk. We have to be willing to open ourselves to be changed by what we read. We cannot read with skepticism, we cannot start a book expecting to disagree with it, we cannot start reading with preconceived notions about what we might expect to find there. (This describes a large portion of the reading—and conversation, and social media use—that is being done today, and online algorithms are no help here.) Instead, we should read as C. S. Lewis outlines in his book An Experiment in Criticism, a book I’d highly recommend on how to think about reading: “The first demand any work of any art makes upon us is surrender. Look. Listen. Receive. Get yourself out of the way. (There is no good asking first whether the work before you deserves such a surrender, for until you have surrendered you cannot possibly find out.)”4 The time for asking questions about a book comes later. The threshold into the liminal space of a book is about getting ourselves, with our received opinions and judgements, out of the way, and coming to the experience of reading as a beginner, a learner. We must stop pretending to be experts in everything.

This might seem frightening, and in fact if you’re not a little frightened of this idea, you probably haven’t fully taken it in. It is nothing less than giving up control, and most of our lives are about maintaining as much control in as many areas as we possibly can. Even a small object made of paper, cloth, glue, and ink represents the very real psychic danger of having to change your mind, to change your life, or at least to be confronted with ideas and values very different from your own. This is not safe.5 We like reading things we know we will already agree with (or hear them on the news, or social media, or from our friends) because it makes us feel safe,6 and confirms that we are right and just and good, which is how all of us like to think of ourselves. Modern life is set up to avoid liminal space at all costs. But in order to get the goodness out of a book, to experience the liminal space that points us toward the greater reality, we must give up control. We must surrender. We must be willing to be wrong.

Suppose now that we have crossed this threshold. We have let go of control and begun reading the book in a spirit of curiosity and discovery. What do we step into? What is that middle state in the liminal space of a rite of passage? This is where I think that wilderness is a helpful metaphor for the liminal space of the reading experience.

For modern, western people, I suppose the most common associations to the word “wilderness” are the beauty of national parks, animals (seen from safe distances), and s’mores around a campfire. This is a cozy picture, and not at all what I mean. There is nothing truly liminal about that. Let’s think instead about Beowulf leaving the safety of Heorot and going out into the darkness where Grendel lurks. King Lear leaving his daughters’ houses and being driven out into the storm on the heath. These are pictures of characters whose lives were endangered by their entrance into a wild place. And in that wild crucible, they were changed.

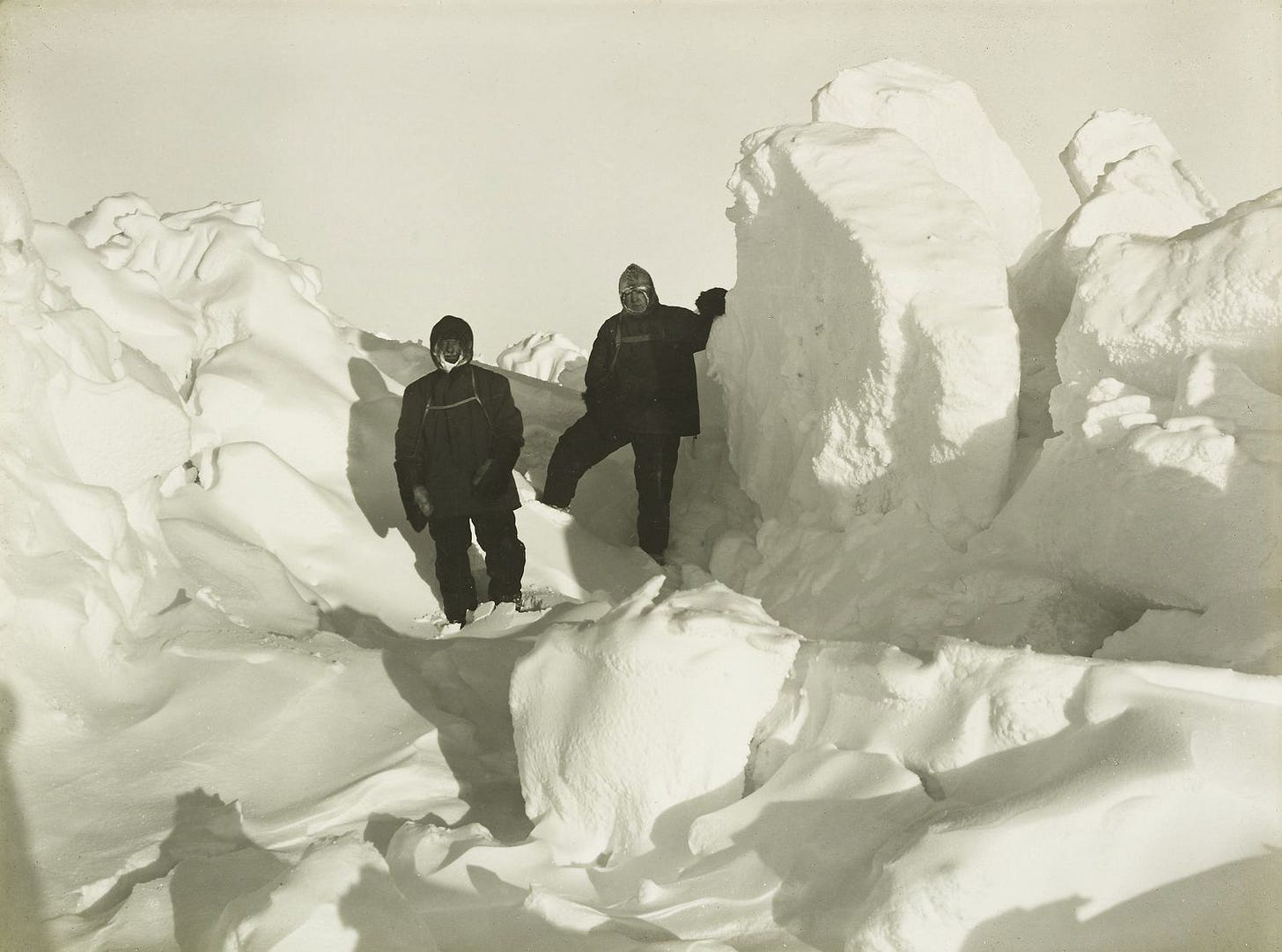

In Ursula Le Guin’s The Left Hand of Darkness, Genly Ai travels to the planet Gethen as an ambassador from the Ekumen, which is something like an intergalactic United Nations, to convince the planet to join their confederation. Doing so requires cooperation between the two opposed kingdoms on the planet, Karhide and Orgoreyn. Ai, who at first does not understand local politics or manners, also cannot see beyond his own experience of gender to understand the Gethenians, who are ambisexual. After unsuccessfully attempting to convince both kingdoms of the wisdom of joining the Ekumen, Ai finds himself in a prison camp, from which he is rescued by Estraven, the ex-prime minister of Karhide, whom Ai does not completely trust. After the prison break, the pair decide to return to Karhide to try to salvage Ai’s mission, and in order to do so, make a dangerous eighty-day journey across the planet’s great ice plain.

Wilderness in these examples is not something to be tamed and controlled, but something uncontrolled that has power over us. We should think not of pioneers conquering nature but of Jonah and the whale, or the Israelites in the desert. The wilderness borders on the world we inhabit, but also borders on another world: a world that is wild, uncontrolled, or even divine. A world that is death for humans to enter.

Wilderness is the place where human beings should not be able to live. It is not the cities, the farms, the places where everyday life and family and routines are carried on. It is not the status quo. In fact, it might be the place where spiritual encounters can occur; and therefore it is a place of peril. Like the religious stories that tell of people venturing into the wilderness or the desert to have a divine encounter, the wilderness exposes our inner realities and makes them visible to us. The liminal space of the wilderness is a place where hearts can be shaped, minds can be changed, transformation can happen. Our normal lives dull us into set patterns and routines, but in the wilderness, we can break through our chrysalis.

Ai and Estraven’s journey across the ice plain is a transformative journey for both of them. For Ai, it is also a journey into the wilderness of his gender identity, as he struggles to understand and relate to an alien who inhabits both genders. Without his experience in the wilderness, Ai would not have understood Estraven; he would not have understood his own maleness with enough clarity to be an effective ambassador to Gethen; and he would not have accomplished his mission to bring the planet into the Ekumen.

The wilderness is an emptying place as well as a place where one can be filled. It is a place where the status quo, and life itself with its normal rhythms and obligations, is stripped away, a place of death that can paradoxically be the doorway to new life. In a rite of passage it is the place where childhood dies so that adulthood can begin. The experience of reading a book is a little death, in that we cease to be ourselves for a time, instead becoming the characters of the book.

So if we leave our selves behind and try on, in The Left Hand of Darkness, Ai’s history and thoughts and desires for a while, then the magic of a book will happen. We may find that seeing through the eyes of Ai shapes our own desires: teaches us to see how he sees and to love what and how he loves. Or we may find that a hidden or shadow part of us which is a bit like Ai comes online through the process, and is thus available to us, enabling us to become more whole.

My friend Cristina Bruns, who studies the interaction between readers and literary texts, talks about books being transitional objects, like a toddler’s teddy bear. Whereas a transitional, or liminal, space is one that “blurs the boundaries between fiction and reality, between self and other, between inner and outer experience”,7 so a transitional object helps navigate the relation between two states. For a toddler, a teddy bear is not fully the toddler’s self, and yet it is; it is not fully the parent, and yet it stands in for the parent. This makes the teddy bear a useful object in the transition all children undergo from understanding themselves as being part of their mother to understanding themselves as a separate individual. The teddy bear straddles both worlds and brings the safety of the mother’s presence into the scary liminal space of her absence—say, at night in the dark of the crib.

If a book is like the transitional, liminal object of a teddy bear in this way, it allows us to die to self in order to blur the boundaries between our inner selves and the outer world, to take down the stone walls of our individualism and experience a little of what it is like to be someone else. And this, says C. S. Lewis, allows us to “seek an enlargement of our being. We want to be more than ourselves. Each of us by nature sees the whole world from one point of view with a perspective and a selectiveness peculiar to himself. . . . We want to see with other eyes, to imagine with other imaginations, to feel with other hearts, as well as with our own.”8 A book therefore can be both a wilderness and also a teddy bear. It is the place of wild uncontrol and the object that makes us feel safe. It is both the desert and the compass that points the way home. It is the tornado that lands us in Oz and the ruby slippers.9

The enlargement of our beings that Lewis talks about does not happen automatically. If we only consume books, devouring them (there are a lot of eating metaphors for reading), then all these good things stay in the liminal space, and will not return with us. We must not just consume books, we must live them. There is a further threshold required to step back out of the wilderness of liminal space—the middle space of the rite of passage—back into our lives; in order to bring the treasure or wisdom that we discovered in the wilderness back with us, we must ask ourselves some questions. In other words, we must contemplate what we read. We might ask: How can the desires the book awakened in me be met in the real world? Can I live it?10 What does this require of me? How can I bring it home? What is this part of me who feels like Ai, and what do I need to learn from her?

We might also re-read. The process of re-reading (and doing so slowly) could be like a trellis for the winding vine of our contemplation to build itself on (a metaphor worthy of its own essay). As we anticipate what we know now will happen in the book, new details might pop out to us; we might find ourselves wondering about choices the author made; we might question in a deeper way the choices the characters make.

Myths and fairy tales are excellent places to see how this process works in miniature. In the story of Cinderella, most little girls when first encountering the story will see themselves as the girl who gets to marry the prince in the end. But we might ask ourselves now: which character are we in the story? Are we Cinderella, whose goodness and kindness are either unrecognized or unappreciated without the magical help of a fairy godmother? Are we the stepmother, who cannot bear the ways in which Cinderella represents what she lacks? Or the stepsisters, who (in the Grimms’ version) will cut off even their big toes to get ahead in life? Or perhaps we feel that we are meant to be the fairy godmother to a young person in our lives. As we read the story again, we let the tale work on us; and reflecting on where we find ourselves in the story leads us back out of the wilderness of liminal space to bring this new knowledge of ourselves to bear in our lives. Perhaps we realize that we need to regrow a toe. That is the kind of realization that will change a life.

One of the books that had an early and immense influence on me was Louisa May Alcott’s Little Women; like many bookish girls, I was Jo March. Because of that novel, I wrote plays that I forced my sister to perform with me; I very briefly wrote a family newspaper (there might have only been one issue); and I read many of the books that Jo is mentioned reading—Jo was my introduction to Dickens, George Eliot, John Bunyan, and possibly Shakespeare. I also found a way to accomplish myself what Jo longed to do and could not—to study abroad in London. That desire would never have been born in me without Jo’s dreams becoming mine the way they did when I read Little Women. Probably to Jo March can also be credited the fact that I have lived in New York City for the past fifteen years. Inhabiting Jo’s thoughts and feelings by reading and rereading that novel gave me not just a vision for a way my life could look, but the courage to step toward it.

Another example, from my mid-twenties, is Edith Wharton’s The House of Mirth. As a young single woman in New York for whom money was a persistent worry, Lily Bart’s story was supremely uncomfortable to me. I remember walking around after I finished the book in a state of mild shock, with the thought that over one hundred years after the novel was published, the most reliable way for a woman to find security for herself was—still—to marry a rich man. Lily could not quite bring herself to do it; neither could she bear the alternative. I was never the type of person who would be tempted to marry a doctor in order to not need to work; but I found that Lily’s story woke me up to thinking about what I wanted in relationships and in life a little bit differently.

The author whose works I have had the longest and deepest relationship with is Shakespeare, both in reading and in seeing the plays performed. I will never forget seeing Ian McKellan play King Lear in 2018, not only because he was brilliant, but because the descent into dementia his performance showed helped me to begin to grieve my father’s recent diagnosis with Alzheimer’s. It opened a door for me to a reality that I had not, until then, been ready to face.

The last thing I want to say about wilderness is this: the mythologist Martin Shaw says that we are changed in two ways: through crisis or through quest.11 In other words, wilderness comes into our lives in two ways. We either seek wilderness, we seek to change, through embarking on a quest; or wilderness and change are thrust upon us through illness or grief or crisis or pain. Books are quests between paper or cloth covers that we can choose to seek out and read to become better people. But books are also the compasses that help us navigate the wildernesses we find ourselves in, no matter how we got there.

In J.R.R. Tolkien, The Monsters and the Critics (HarperCollins, 2013): 148.

The Return of the King (HarperCollins, 2017), Book 6, Chapter 2: 1206.

https://www.ursulakleguin.com/nbf-medal

C. S. Lewis, An Experiment in Criticism (Cambridge University Press, 1961): 19.

I'm tempted to quote C. S. Lewis again here: it is not safe, but it is good.

Cristina Bruns notes that this is why formulaic fiction is so popular; “Reading Readers: Living and Leaving Fictional Worlds,” NARRATIVE 24.3 (2016): 326.

Why Literature?: The Value of Literary Reading and What It Means for Teaching (Continuum, 2011): 25.

An Experiment in Criticism, 137. Bruns and Paul Ricoeur make the same argument.

Silver, of course, in the original book.

See also Mark Edmundson, Why Read? (Bloomsbury, 2005).

I wish I could find again where he said this. I suspect it was in a podcast interview, but possibly also on his excellent Substack, The House of Beasts & Vines.

This was great. Eagerly awaiting part two!